- How can a virus be so selective? How can the heterosexual epidemic largely be confined to a few southern African countries?

- Why has the virus only led to a “heterosexual epidemic” in southern Africa?

- Who is at risk of being infected? How can the heterosexual epidemic largely be confined to a few southern African countries?

The preceding post tracks the analyses that dispute the representation that a new viral cause of disease ravaged South Africa since the early 1990s. In this post I look at how HIV allegedly discriminates in terms of who is infected – another aspect where reality and representation do not correlate.

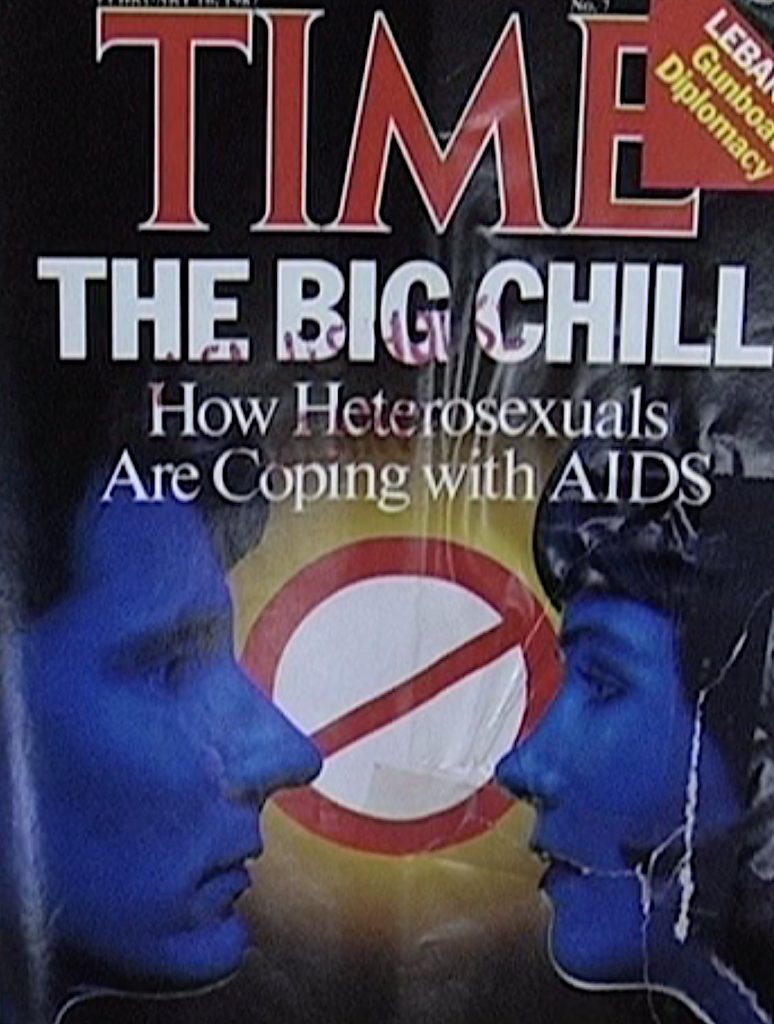

Globally, in the early 1990s, Aids was portrayed as an epidemic spreading into the heterosexual population. But by 1996, the controversy over the potential causative role of drug use in Aids resurfaced: 80% of documented Aids cases in the West were heavy recreational drug users. As an example, a San Francisco study demonstrated that 82% of Aids patients in that city were taking poppers (amyl nitrate), which was later banned due to being highly toxic, and 3% were heroin users. According to US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) data, only 5% of new Aids cases were heterosexuals and they were also drug users, investigative journalist Janine Robert reports. (Roberts 2006).

However, on 1 May 1996, in “Aids fight is skewed by Federal bodies exaggerating risks”, the Wall Street Journal published an expose of the political decision of the CDC to create the impression that heterosexuals were at risk of contracting HIV, even though they were well aware that testing HIV positive was largely confined to risk groups, including intravenous drug users and homosexuals, who made up 90% of US cases. The CDC was forced to admit that they had spread a lie that HIV posed a heterosexual threat, motivated – they claimed – out of a desire not be perceived as homophobic, as well as to ensure that funding from Congress would continue to flow (Roberts 2006). In Between the Bands (BtB), Rawlins explains that Kevin de Kock, then director of HIV/Aids at the WHO, acknowledged in 2008 that there had never been a heterosexual epidemic globally, except in southern Africa, which reaffirmed the CDC’s forced acknowledgement. How can a sexually transmitted infection discriminate in this way?

HIV appears to discriminate by race

By analysing the results of testing large cohorts in the US, Henry Bauer notes that, even when controlling for variables such as health condition, occupation and socio-economic status, black people, on average, tend to test positive five to six times more often than people of Asian or European descent (2007: 50). The ratio of testing positive between black and white is 2.8 at public sites (sample size of 2.2 million), 7.9 in applicants testing for the military (one sample group was 6.9 million), 12.2 in pregnant women (from a sample group of 14.5 million) and 14 in blood donors (from a sample group of 2.2 million), thus new mothers and blood donors revealed the greatest disparity between black and white, though a more consistent overall ratio would be expected if the sample were taken from a group matched by age, sex and location (2007: 50). In 1989, the CCD conceded that geographically this racial pattern is consistent in each state of the US and in 1991 reported the racial disproportion in women: stating that in those with no apparent risk factors, black women were between three and 28 times more likely to test HIV-positive. Black drug abusers also had a five-fold higher chance of testing HIV positive than white counterparts (CDC 1991 cited by Bauer 2007: 57).

In 2004, in South Africa a scandal broke out when it was discovered that blood donated by black people was automatically categorised as high-risk and, except for the plasma, was barred from being used. Thus, after the plasma had been removed, the rest was incinerated. In an article by Lindsay Barnes on 12 March, titled “Black blood burnt”, it was reported that on average the likelihood of testing HIV positive for black South Africans was 100% higher than white nationals and even as high as 150% in some groups. While in South Africa black women are 100-fold likely to test positive than white women, in the US it is 35-fold (Barnes 2005 cited by Bauer 2007: 246).

Behavioural justification for the racial discrepancy is unsubstantiated and racist

The marked racial and ethnic differences in HIV prevalence, even among persons treated in the same clinic, suggests that both behavioural norms and complex social mixing patterns within racial and ethnic groups are important determinants of HIV transmission risk.

(CDC 1992:37 cited by Bauer 2007: 74).

Commenting on the racial disparities in the US, Bauer writes that the “only interpretation” feasible within the theory that HIV is a sexually transmitted virus is that “having African ancestry, by contrast to Caucasian, increases by a factor of five or six the probability that one will practice unsafe promiscuous sex or share infected needles with HIV-positive people. […] Such an assertion is the epitome of racism” (Bauer 2007: 74).

To justify that HIV is sexually transmitted in Africa, these same ideas of a racial tendency to engage in risky sexual practices is evoked. Yet in footage not included in BtB, Rawlins cites studies that show British and Americans to be more sexually promiscuous than black Africans. Although sexually transmitted diseases were on the increase in the 2000s in England, for example, this did not lead to an increase in the rate of testing HIV-positive. In BtB, Brink also discusses the profound racism that underpins the belief that black people in South Africa are more promiscuous than other races despite no evidence to support this.

Has HIV been proven to be sexually and vertically transmitted? The Perth Group’s analysis leads to a resounding: no.

A key tenet of the HIV and Aids theory is that the virus is sexually and vertically transmitted but this has been challenged. In the US, Nancy Padian and colleagues spent a decade running a study of heterosexual transmission (Padian et al 1997). The researchers tracked 175 discordant couples over “a total of approximately 282 couple-years. […] The longest duration of follow-up was 12 visits (six years).” There were no new infections during the study.

Padian, and colleagues, then used data from presumed conversions in HIV-positive couples she had studied previously. Based on the assumption they had been infected through heterosexual sex she came up with an estimation of “the risk of HIV infection ‘through male to female contact’ as ‘0.0009’.” The late Professor Mhlongo wrote that this estimated transmission rate means it would take 770 sexual contacts to reach a 50%, or 3,333 sexual contacts to reach a 95%, probability of becoming infected. With female-to-male transmission, the risk of infection is much lower, requiring 6,200 and 27,000 contacts, and a period of 51 and 222 years respectively, to reach a 50% or 95% probability of becoming infected, according to Padian’s estimates, based on presumed transmission (Mhlongo 14 March 2003). This comment was made in a debate on the rapid response pages of the British Medical Journal (BMJ), as were many other citations in this blog.

Due to the increased use of condoms over time in the Padian study, in the rapid response debate, (responding to a 2003 article by Didier Fassin and Helen Schneider, “The politics of AIDS in South Africa: beyond the controversies”, which went on for a few years), some challengers in the orthodox camp wrote that this study does not not prove transmission, to which the Perth group countered, in that case where is the study that proves HIV is sexually transmitted? They pointed out that at the time there were no prospective studies that evince bidirectional sexual transmission of HIV (Papadopulos-Eleopulos et al. 24 March 2003).

Based on their analysis of the data, researchers Gisselquist et al. concluded that HIV is not transmitted by sex, but only by specific risky practices, specifically referring to passive anal intercourse. Papadopulos-Eleopulos et al. comment that while the data shows that this form of sex can lead to a positive result on the non-specific HIV test, they stress that no proof exists that the alleged virus can be transmitted to the active partner (Eleopulos et al. 24 March 2003).

Bi-directionality: a basic condition for sexual transmission of a virus

Papadopulos-Eleopulos et al. point out that bi-directionality is an essential prerequisite for viruses to be transmitted sexually. In the Padian study two factors stepped up the risk of transmission; anal intercourse and being of a non-white race. Padian has also commented that only in sub-Saharan Africa is penile-vaginal transmission touted as the cause of the rapid spread of HIV and Aids (Papadopulos-Eleopulos et al. 13 March 2003).

That HIV is not a bi-directionally transmitted infectious agent is backed up by data on adult Aids cases in New York. Journalist Celia Farber reports that in 1990 there was a single reported case of female-to-male transmission. Between 1981 and 1992, although there were 30,493 cases of men with Aids there were only 12 recorded cases of female-to-male transmission. Then, in 1993 the New York City Health Department changed their data collection methodology, making it impossible to ascertain this type of detail (Farber 2006B: 175).

A few years after the Padian study results were published, Chakraborty et al. did a meta-analysis assessing the rate of sexual transmission in various US and European studies, concluding that the estimated chance of transmission of HIV to be one in a thousand per sex act (2001). In BtB, in an audio clip in the opening sequence of the film, Dr Francois Venter, without a trace of irony, states this another way; that a person has to have sex every night for three years to run the risk of that one in a thousand chance of contracting HIV.

Bauer deduces, based on the Chakraborty analysis, that the probability of transmission of HIV is clearly so insignificant it is hard to fathom how this could possibly be seen as the cause of an epidemic of this alleged scale. He then argues that the reason the low transmission rate detected in these studies did not cause the HIV theory of Aids to be questioned is because HIV research is spread over various scientific fields that span virology, immunology and epidemiology, with immense mutual respect between colleagues in different areas of specialisation. Thus, when a particular research group finds baffling anomalies in one field, they argue that further research is needed to explain them, since if the anomalies were truly indicative of fault lines in the scientific evidence this would imply that there were problems with the other fields of research relating to HIV too (2007: 163). Bauer also reminds us that in the case of other alleged sexually transmitted diseases (STDs,) such as gonorrhoea and syphilis, although the probability of transmission is considered to be hundreds of times greater, these diseases have not caused epidemics in the way that it is said HIV has.

The post-1988 consensus that ascribed over 90% of adult HIV to heterosexual transmission and an insignificant proportion to unsafe injections was not at the time – or later – supported by calculations from evidence associating HIV with sexual behaviours. Instead, the numerical estimate seems to have been derived by a process of elimination. […] Influential epidemiologic reviews published between 1987 and 1990 presented a variety of inferential arguments and hypothesis to support consensus estimates of sexual transmission.

Gisselquist et al. 2003 quoted by Rasnick, 26 April 2003

Chakraborti et al’s estimate of male-to-female probability of transmission being one in a 1000 chance per sex act was deduced from empirical studies. Then, he and co-researchers constructed a model based on many assumptions, including “an uncritical acceptance of the uncontrolled HIV-1 viral load data for seminal plasma” from various studies, to come up with a probability of sexual transmission 10 times greater, which brought the odds down to 1 per 100 episodes of sex, as pointed out by David Rasnick (26 Apr 2003). This 10-fold higher than observed probability rate formed the basis of a CDC report that stated that the risk of HIV transmission per episode of receptive vaginal exposure was estimated to be 0.1% to 0.2% (CDC 1998). In 2000, Mbeki also remarked that there was no empirical base for this estimate (Brink 2001:71).

The low transmission rate Chakraborty et al. initially observed was borne out over two decades of studies in four countries, which included African, that all show a rate of no more than a few per 1000, which would be accounted for more realistically as seroconversion rates in risk groups owing to exposure to health challenges rather than infection of a sexually transmitted disease, Bauer asserts (2007: 44-5).

Dispassionate assessment of our conclusions admittedly depends on a willing suspension of disbelief, since the current paradigm is deeply embedded. Counter arguments can (and will) be levelled at each of the anomalies noted, but the depth and breadth of concerns deserve fair scrutiny. At issue in a re-evaluation of the heterosexual hypothesis are the profound implications for our interventive approach, and for the kind of social and financial commitments that must be made. Finally Africans deserve scientifically sound information on the epidemiologic determinants of their calamitous Aids epidemic. (Brewer et al. 2003 quoted by Rasnick, D. 26 April 2003)

The mounting toll of HIV infection in Africa is paralleled by a mounting number of anomalies in the many studies seeking to account for it. […] We are aware of no study from sub-Saharan Africa suggesting cyclic sexual network architecture. Without evidence of appropriate network configurations on a scale considerably larger than that observed in developed countries, rapid propagation of HIV in Africa would be difficult to sustain. […] Similarly, there are persistent reports of HIV in infants with seronegative mothers.

Brewer et al. 2003

Thus, many orthodox researchers, including Chakraborty, Gisselquist, Brewer, Potterat, and their colleagues, had been highlighting the fundamental paradox; namely, the lack of evidence that HIV is transmitted sexually, or that the virus is transmitted from mothers to babies. The Perth Group also argue that since neither the clinical condition (since it has been shown that HIV-positive babies and HIV-negative babies die from the same diseases) nor the death of a child can be used to prove infection or mother to child transmission (MTCT), it is not possible to establish MTCT (Papadopulos et al. 2001: 59) These researchers have been calling for a reappraisal of the tenet that HIV is sexually or vertically transmitted. The Perth Group go further, their analysis of the foundational experiments in which HIV was allegedly isolated led them to the conclusion that HIV has not been proven to exist.

No correlation between sexually transmitted diseases and testing positive

In BtB, Rawlins makes the point that the epidemiological representation that the Aids epidemic became largely confined to black people in South Africa makes no sense, if HIV was a sexually transmitted virus. He cites studies that show that British and Americans are more promiscuous than Africans and yet it is put forward that the reason for the excessive spread of the virus in Southern Africa is due to sexual behaviour. He also cites studies showing that sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) were rising in Britain, for example, and yet this has not resulted in a concurrent increase in testing positive for HIV. This is corroborated by studies; for example, on 27 July 2004, BBC News reported on Health Protection Agency data indicating that the incidence of STDs had risen in the UK by 4% in 2003 – the most common being Chlamydia, which increased by 9%. Why, researcher Alexander H. Russell asks, was there no mention of figures for the HIV infection rate? (Russell, 5 August 2004).

In South Africa, a study of pregnant women showed no correlation between syphilis and testing HIV-positive. Strangely, an inverse correlation between the two exist in some South African provinces; in KwaZulu-Natal, which has the highest HIV rate, the prevalence of syphilis was the lowest, while in the Western Cape, in 2000 the recorded rate of syphilis was the highest for the country but this province had the lowest HIV rate. The same discrepancy is found in Thailand. Bangkok has the highest rate of STDs but low HIV prevalence, whilst in contrast the so-called ‘Golden Triangle’ of northern Thailand (infamous for opium, and hence drug abuse is far worse) has the highest rate of HIV but the second lowest STD morbidity (Rasnick, 23 April 2003). Bauer also found that the chance of infection with an STD is greater in prostitutes than the general population but they only show a high likelihood of testing HIV-positive if drug abuse is involved (Bauer 2007: 86).

The question that arises: did HIV or drugs caused them to test positive?

Roberts notes that the notion of heterosexual spread in developed countries is still propagated in disingenuous reports, such as an official release in the UK in 2004, which stated that most new cases of infection were transmitted via heterosexual intercourse. However, Roberts finds entirely the opposite in the fine print: ‘Men-having-sex-with-men (MSM) remain the group at greatest risk of acquiring HIV infection within the UK, accounting for an estimated 84% of infections diagnosed in 2003 that were likely to have been acquired in the UK’. Of 6,606 incidents of HIV infection recorded that year, a mere 43 had been British women and only 57 were British heterosexual men. The majority of female and heterosexuals that made up the figure were in fact immigrants from Africa and, as Roberts writes, they was presumed to have become positive in their countries of origin, yet why does the virus affect African people more than whites, Roberts logically asks (Roberts 2006: 9). As noted, Bauer’s analysis shows that people with African ancestry have a greater propensity to test positive and considering that the transmission rate data is under question, these researchers think there must be other factors that cause black people to be more likely to test positive.

Orthodox scientists and doctors espouse racists beliefs

In the representation of Aids, this syndrome is differentiated from other infectious diseases as follows:

…it is lethal and incurable….it is a life-long infection with life-long infectiousness and… infectivity is so low that the risk of infection can voluntarily be virtually eliminated by the behaviours and habits of the individual[…] Because the transmissibility of the virus is so low, it implies that the majority of infected individuals have acquired infection by their own free will choice and therefore would have only themselves to blame. It aggravates the victimisation of the infected individuals and those perceived by society to be at risk of infection, who are then blamed for the spread of the disease and for placing the ‘rest’ of society at risk of being ‘involuntarily’ infected, for example by blood transfusion (Schoub 1999: 206-7).

This racist inference of promiscuity in black people is not rooted in evidence, with Bauer noting that research has not shown differences in sexual behaviour between the races. In the US, the hypothesis that a proportion of heterosexual black men are engaging in clandestine homosexual behaviour (known as living on the ‘down-low’) has been promulgated to explain why HIV has spread more among black people. However, no evidence has been presented of this (Bauer 2007: 76).

In the West, HIV infection has largely been contained to risks groups, which is not what you would expect from a sexually transmitted epidemic. In the late 1990s, it was reported that the epidemic was raging in central Africa. Yet, as noted, in many countries including South Africa, the purported epidemic was based on highly inflated estimates. It is puzzling that a sexually transmitted epidemic would be having such an uneven impact on the continent and globally, with some countries barely impacted. In 2007, South Africa was among eight countries in the sub-Saharan region that allegedly accounted for two thirds of the global HIV burden (UNAIDS. 2007).

Former emeritus professor of Public Health at the University of Glasgow, and prior World Health Organisation (WHO)s adviser on Aids, Gordon Stewart, projected that Aids would be limited to the original risk groups, and his forecasts have been correct to within 10%, when examining actual data and not looking at modelled projections. As early as 1987, Stewart commented that the epidemiological data did not substantiate the claim that Aids was transmitted heterosexually.

Despite being an advisor to the WHO, when he submitted this argument in a paper, it was “barred from publication” at the very time when the epidemiological projections were igniting a wave of global panic, explained UK journalist Neville Hodgkinson, citing Stewart’s work (Stewart 1999 cited by Hodgkinson 2003). In 1990, Stewart warned the British Department of Health that the predictions were greatly amplified in comparison to the actual data. The Royal Society rejected a paper he sent them and, aside from a short letter in the Lancet, his papers were turned down by several journals. However, by the end of the 1990s his predictions turned out to be very accurate for Britain, explains filmmaker and writer Joan Shenton (1998: 70-1). When an essay was printed in the UK Times, after Stewart’s censorship had been documented in a book by Hodgkinson (1996), Stewart was finally invited by the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London to submit a paper but even this solicited paper was ultimately unpublished (Bauer 2007: 230-1).

In an unpublished review, Stewart noted that from 1982 to 1998 in the US, 75% of the recorded Aids cases were in high-risk groups and 99% of the 1,789 infant Aids cases in the same time-frame had mothers in high-risk groups. Stewart’s analysis led him to conclude that in the US,

…perinatal and neonatal Aids are minimal except where mothers and infants are exposed to risks in ethnic, drug-using and bisexual situations. After 20 years of intensive surveillance in a country where Aids is as prevalent as in some third world countries, this in itself excludes any appreciable spread of Aids by heterosexual transmission of HIV in the huge majority of the general population (Stewart. 2000 cited by Hodgkinson, 2003).

In the case of South Africa, the tragedy is that from the Apartheid to the post-Apartheid era there was no new cause of death. Disease and death continued to be largely caused by poverty, malnutrition, lack of basic hygiene etc. (in addition to an increase in lifestyle-related disease) and yet a considerable portion of our national health budget has been funnelled into testing and treatment with toxic drugs. It turns out our much-maligned former President Thabo Mbeki was right all along.

Representation of HIV not in sync with reality

HIV/ Aids has continued to be represented as invariably fatal, with toxic “antiretrovirals” providing a stop-gap measure to allegedly delay death and shift the syndrome to chronic. This has been despite:

- the non-specificity of the tests, which directly links to the issue of isolation,

- the analyses of the epidemiology not finding evidence of a new cause of death in the form of a sexually transmitted virus, and

- the negligible proof of transmission.

At the Presidential Aids Advisory Panel convened by then South African President Thabo Mbeki in 2000, he raised the question of how the virus is able to discriminate. Rasnick comments that Mbeki was heavily criticised by the media due to asking these questions:

- Why is Aids in Africa so completely different from Aids in the US and Europe?

- How does a virus know to cause different diseases on different continents?

- How does a virus know if you are male or female, gay or straight, white or black?

Yet Mbeki was echoing the question raised in papers published in scientific journals. In the next blog post, we look at the representation of HIV and Aids and how the combination of exaggerated projections and stark imagery shaped a sense of identification.